Im Against Political Crectnees It Allows Me to Be Racist Again

T hree weeks agone, around a quarter of the American population elected a demagogue with no prior experience in public service to the presidency. In the optics of many of his supporters, this lack of training was not a liability, but a strength. Donald Trump had run as a candidate whose main qualification was that he was non "a politician". Depicting yourself as a "maverick" or an "outsider" crusading against a decadent Washington institution is the oldest play tricks in American politics – but Trump took things further. He broke countless unspoken rules regarding what public figures can or cannot do and say.

Every demagogue needs an enemy. Trump's was the ruling elite, and his charge was that they were not only failing to solve the greatest problems facing Americans, they were trying to stop anyone from fifty-fifty talking near those problems. "The special interests, the arrogant media, and the political insiders, don't desire me to talk about the criminal offence that is happening in our country," Trump said in one late September spoken language. "They desire me to just keep with the same failed policies that accept acquired so much needless suffering."

Trump claimed that Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton were willing to permit ordinary Americans suffer considering their first priority was political correctness. "They accept put political correctness above common sense, higher up your safety, and above all else," Trump declared after a Muslim gunman killed 49 people at a gay nightclub in Orlando. "I refuse to exist politically correct." What liberals might accept seen equally language irresolute to reflect an increasingly diverse society – in which citizens attempt to avert giving needless offence to one another – Trump saw a conspiracy.

Throughout an erratic campaign, Trump consistently blasted political definiteness, blaming it for an extraordinary range of ills and using the phrase to deflect any and every criticism. During the first debate of the Republican primaries, Flim-flam News host Megyn Kelly asked Trump how he would answer the accuse that he was "part of the state of war on women".

"You've called women you don't similar 'fatty pigs,' 'dogs,' 'slobs,' and 'icky animals'," Kelly pointed out. "Yous once told a contestant on Celebrity Apprentice it would be a pretty pic to see her on her knees …"

"I recollect the large trouble this country has is being politically correct," Trump answered, to audience applause. "I've been challenged by so many people, I don't frankly have time for full political definiteness. And to exist honest with you lot, this land doesn't have time either."

Trump used the aforementioned defence when critics raised questions about his statements on immigration. In June 2015, subsequently Trump referred to Mexicans as "rapists", NBC, the network that aired his reality testify The Apprentice, announced that it was catastrophe its relationship with him. Trump's team retorted that, "NBC is weak, and similar everybody else is trying to be politically right."

In Baronial 2016, after maxim that the Usa district judge Gonzalo Curiel of San Diego was unfit to preside over the lawsuit against Trump Universities because he was Mexican American and therefore likely to be biased against him, Trump told CBS News that this was "common sense". He connected: "We have to end being and so politically correct in this country." During the second presidential debate, Trump answered a question about his proposed "ban on Muslims" past stating: "We could exist very politically right, but whether we like it or non, there is a problem."

Every time Trump said something "outrageous" commentators suggested he had finally crossed a line and that his entrada was now doomed. Simply time and once more, Trump supporters made it clear that they liked him considering he wasn't afraid to say what he idea. Fans praised the style Trump talked much more often than they mentioned his policy proposals. He tells it similar it is, they said. He speaks his listen. He is not politically correct.

Trump and his followers never defined "political definiteness", or specified who was enforcing it. They did not take to. The phrase conjured powerful forces determined to suppress inconvenient truths by policing linguistic communication.

In that location is an obvious contradiction involved in lament at length, to an audience of hundreds of millions of people, that y'all are being silenced. Simply this idea – that at that place is a set of powerful, unnamed actors, who are trying to control everything you do, right downward to the words you use – is trending globally right now. Great britain's rightwing tabloids consequence frequent denunciations of "political correctness gone mad" and rail against the smug hypocrisy of the "metropolitan elite". In Germany, conservative journalists and politicians are making like complaints: afterward the assaults on women in Cologne last New year's day's Eve, for instance, the master of police force Rainer Wendt said that leftists pressuring officers to be politisch korrekt had prevented them from doing their jobs. In French republic, Marine Le Pen of the Front National has condemned more traditional conservatives every bit "paralysed by their fear of confronting political correctness".

Trump'due south incessant repetition of the phrase has led many writers since the election to fence that the secret to his victory was a backlash against excessive "political definiteness". Some accept argued that Hillary Clinton failed considering she was too invested in that close relative of political correctness, "identity politics". But upon closer examination, "political correctness" becomes an impossibly slippery concept. The term is what Ancient Greek rhetoricians would have called an "exonym": a term for another group, which signals that the speaker does not belong to information technology. Nobody e'er describes themselves every bit "politically correct". The phrase is only ever an allegation.

If you say that something is technically right, you are suggesting that it is wrong – the adverb before "correct" implies a "merely". Still, to say that a statement is politically correct hints at something more insidious. Namely, that the speaker is acting in bad faith. He or she has ulterior motives, and is hiding the truth in order to advance an calendar or to bespeak moral superiority. To say that someone is being "politically correct" discredits them twice. Beginning, they are wrong. Second, and more damningly, they know it.

If yous go looking for the origins of the phrase, information technology becomes articulate that there is no keen history of political correctness. There have but been campaigns against something called "political definiteness". For 25 years, invoking this vague and ever-shifting enemy has been a favourite tactic of the right. Opposition to political definiteness has proved itself a highly constructive form of crypto-politics. It transforms the political landscape past interim as if it is non political at all. Trump is the deftest practitioner of this strategy yet.

One thousand ost Americans had never heard the phrase "politically correct" earlier 1990, when a moving ridge of stories began to appear in newspapers and magazines. One of the first and nigh influential was published in October 1990 by the New York Times reporter Richard Bernstein, who warned – under the headline "The Rising Hegemony of the Politically Correct" – that the country'south universities were threatened by "a growing intolerance, a endmost of debate, a pressure level to adapt".

Bernstein had recently returned from Berkeley, where he had been reporting on student activism. He wrote that there was an "unofficial ideology of the university", according to which "a cluster of opinions most race, ecology, feminism, culture and foreign policy defines a kind of 'correct' attitude toward the issues of the globe". For instance, "Biodegradable garbage bags go the PC seal of approval. Exxon does non."

Bernstein's alarming acceleration in America's newspaper of record ready off a concatenation reaction, as one mainstream publication after another rushed to denounce this new trend. The following month, the Wall Street Journal columnist Dorothy Rabinowitz decried the "brave new world of ideological zealotry" at American universities. In December, the cover of Newsweek – with a circulation of more than 3 meg – featured the headline "Idea POLICE" and yet another ominous warning: "In that location's a 'politically correct' mode to talk about race, sexual activity and ideas. Is this the New Enlightenment – or the New McCarthyism?" A similar story graced the encompass of New York magazine in January 1991 – within, the magazine proclaimed that "The New Fascists" were taking over universities. In April, Time mag reported on "a new intolerance" that was on the ascent across campuses nationwide.

If you lot search ProQuest, a digital database of Usa magazines and newspapers, you notice that the phrase "politically correct" rarely appeared before 1990. That year, information technology turned upward more than 700 times. In 1991, there are more than 2,500 instances. In 1992, it appeared more than 2,800 times. Similar Indiana Jones movies, these pieces called up enemies from a melange of old wars: they compared the "thought constabulary" spreading terror on academy campuses to fascists, Stalinists, McCarthyites, "Hitler Youth", Christian fundamentalists, Maoists and Marxists.

Many of these articles recycled the same stories of campus controversies from a handful of elite universities, oft exaggerated or stripped of context. The New York magazine comprehend story opened with an account of a Harvard history professor, Stephan Thernstrom, being attacked by overzealous students who felt he had been racially insensitive: "Whenever he walked through the campus that spring, down Harvard's brick paths, under the biconvex gates, past the fluttering elms, he institute it hard not to imagine the pointing fingers, the whispers. Racist. There goes the racist. It was hellish, this persecution."

In an interview that appeared soon after in The Nation, Thernstrom said the harassment described in the New York article had never happened. There had been 1 editorial in the Harvard Crimson student paper criticising his decision to read extensively from the diaries of plantation owners in his lectures. But the clarification of his harried state was pure "creative licence". No matter: the epitome of higher students conducting witch hunts stuck. When Richard Bernstein published a book based on his New York Times reporting on political correctness, he called information technology Dictatorship of Virtue: Multiculturalism and the Boxing for America'south Time to come – a championship alluding to the Jacobins of the French Revolution. In the book he compared American higher campuses to French republic during the Reign of Terror, during which tens of thousands of people were executed within months.

Northward one of the stories that introduced the menace of political correctness could pinpoint where or when information technology had begun. Nor were they very precise when they explained the origins of the phrase itself. Journalists frequently mentioned the Soviets – Bernstein observed that the phrase "smacks of Stalinist orthodoxy"– but there is no exact equivalent in Russian. (The closest would be "ideinost", which translates as "ideological definiteness". Simply that word has zip to do with disadvantaged people or minorities.) The intellectual historian LD Burnett has plant scattered examples of doctrines or people being described equally "politically correct" in American communist publications from the 1930s – usually, she says, in a tone of mockery.

The phrase came into more widespread use in American leftist circles in the 1960s and 1970s – most likely as an ironic borrowing from Mao, who delivered a famous speech in 1957 that was translated into English with the championship "On the Right Handling of Contradictions Among the People".

Ruth Perry, a literature professor at MIT who was active in the feminist and civil rights movements, says that many radicals were reading the Little Scarlet Volume in the belatedly 1960s and 1970s, and surmises that her friends may have picked up the adjective "correct" there. But they didn't utilize it in the manner Mao did. "Politically correct" became a kind of in-joke among American leftists – something you lot called a fellow leftist when you thought he or she was beingness self-righteous. "The term was ever used ironically," Perry says, "ever calling attention to possible dogmatism."

In 1970, the African-American author and activist Toni Cade Bambara, used the phrase in an essay about strains on gender relations within her community. No matter how "politically correct" her male friends thought they were being, she wrote many of them were failing to recognise the plight of blackness women.

Until the late 1980s, "political definiteness" was used exclusively within the left, and almost always ironically as a critique of excessive orthodoxy. In fact, some of the first people to organise against "political correctness" were a grouping of feminists who called themselves the Lesbian Sexual activity Mafia. In 1982, they held a "Speakout on Politically Wrong Sexual practice" at a theatre in New York'southward East Village – a rally against beau feminists who had condemned pornography and BDSM. Over 400 women attended, many of them wearing leather and collars, brandishing nipple clamps and dildos. The author and activist Mirtha Quintanales summed up the mood when she told the audience, "We need to have dialogues well-nigh S&M issues, non about what is 'politically correct, politically incorrect'."

By the end of the 1980s, Jeff Chang, the journalist and hip-hop critic, who has written extensively on race and social justice, recalls that the activists he knew and then in the Bay Area used the phrase "in a jokey way – a way for one sectarian to dismiss another sectarian's line".

Simply presently plenty, the term was rebranded past the correct, who turned its significant inside out. All all of a sudden, instead of being a phrase that leftists used to check dogmatic tendencies within their movement, "political definiteness" became a talking bespeak for neoconservatives. They said that PC constituted a leftwing political programme that was seizing control of American universities and cultural institutions – and they were adamant to stop it.

T he correct had been waging a campaign confronting liberal academics for more than a decade. Starting in the mid-1970s, a handful of conservative donors had funded the creation of dozens of new thinktanks and "training institutes" offering programmes in everything from "leadership" to circulate journalism to direct-postal service fundraising. They had endowed fellowships for conservative graduate students, postdoctoral positions and professorships at prestigious universities. Their stated goal was to challenge what they saw as the authority of liberalism and attack left-leaning tendencies inside the academy.

Starting in the late 1980s, this well-funded conservative movement entered the mainstream with a series of improbable bestsellers that took aim at American higher education. The first, by the University of Chicago philosophy professor Allan Bloom, came out in 1987. For hundreds of pages, The Endmost of the American Mind argued that colleges were embracing a shallow "cultural relativism" and abandoning long-established disciplines and standards in an effort to announced liberal and to pander to their students. It sold more than 500,000 copies and inspired numerous imitations.

In April 1990, Roger Kimball, an editor at the conservative journal, The New Criterion, published Tenured Radicals: How Politics Has Corrupted our Higher Education. Like Bloom, Kimball argued that an "assault on the canon" was taking place and that a "politics of victimhood" had paralysed universities. As evidence, he cited the existence of departments such equally African American studies and women's studies. He scornfully quoted the titles of papers he had heard at academic conferences, such as "Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl" or "The Lesbian Phallus: Does Heterosexuality Exist?"

In June 1991, the young Dinesh D'Souza followed Bloom and Kimball with Illiberal Education: the Politics of Race and Sex on Campus. Whereas Bloom had bemoaned the rise of relativism and Kimball had attacked what he called "liberal fascism", and what he considered frivolous lines of scholarly inquiry, D'Souza argued that admissions policies that took race into consideration were producing a "new segregation on campus" and "an attack on bookish standards". The Atlantic printed a 12,000 word excerpt as its June cover story. To coincide with the release, Forbes ran another commodity past D'Souza with the championship: "Visigoths in Tweed."

These books did not emphasise the phrase "political correctness", and only D'Souza used the phrase directly. Just all three came to exist regularly cited in the overflowing of anti-PC articles that appeared in venues such as the New York Times and Newsweek. When they did, the authors were cited every bit neutral regime. Countless manufactures uncritically repeated their arguments.

In some respects, these books and articles were responding to 18-carat changes taking place within academia. Information technology is true that scholars had become increasingly sceptical virtually whether it was possible to talk about timeless, universal truths that lay beyond language and representation. European theorists who became influential in United states of america humanities departments during the 1970s and 1980s argued that private feel was shaped past systems of which the individual might not exist enlightened – and particularly by language. Michel Foucault, for instance, argued that all noesis expressed historically specific forms of power. Jacques Derrida, a frequent target of conservative critics, practised what he chosen "deconstruction", rereading the classics of philosophy in social club to bear witness that even the most seemingly innocent and straightforward categories were riven with internal contradictions. The value of ideals such as "humanity" or "liberty" could not be taken for granted.

It was also truthful that many universities were creating new "studies departments", which interrogated the experiences, and emphasised the cultural contributions of groups that had previously been excluded from the academy and from the canon: queer people, people of colour and women. This was not and so foreign. These departments reflected new social realities. The demographics of college students were changing, considering the demographics of the United States were changing. By 1990, merely 2-thirds of Americans under 18 were white. In California, the freshman classes at many public universities were "majority minority", or more than 50% non-white. Changes to undergraduate curriculums reflected changes in the student population.

The responses that the conservative bestsellers offered to the changes they described were disproportionate and oftentimes misleading. For case, Bloom complained at length nearly the "militancy" of African American students at Cornell University, where he had taught in the 1960s. He never mentioned what students demanding the creation of African American studies were responding to: the biggest protestation at Cornell took identify in 1969 after a cross burning on campus, an open up KKK threat. (An arsonist burned down the Africana Studies Center, founded in response to these protests, in 1970.)

More than any detail obfuscation or omission, the nearly misleading aspect of these books was the fashion they claimed that only their adversaries were "political". Bloom, Kimball, and D'Souza claimed that they wanted to "preserve the humanistic tradition", every bit if their bookish foes were vandalising a canon that had been enshrined since fourth dimension immemorial. But canons and curriculums have ever been in flux; even in white Anglo-America in that location has never been whatsoever one stable tradition. Moby Dick was dismissed equally Herman Melville's worst book until the mid-1920s. Many universities had only begun offering literature courses in "living" languages a decade or so before that.

In truth, these crusaders against political definiteness were every bit equally political equally their opponents. As Jane Mayer documents in her volume, Dark Coin: the Hidden History of the Billionaires Backside the Rise of the Radical Right, Bloom and D'Souza were funded past networks of conservative donors – particularly the Koch, Olin and Scaife families – who had spent the 1980s edifice programmes that they hoped would create a new "counter-intelligentsia". (The New Criterion, where Kimball worked, was also funded by the Olin and Scaife Foundations.) In his 1978 book A Fourth dimension for Truth, William Simon, the president of the Olin Foundation, had called on conservatives to fund intellectuals who shared their views: "They must be given grants, grants, and more grants in commutation for books, books, and more books."

These skirmishes over syllabuses were part of a broader political programme – and they became instrumental to forging a new alliance for bourgeois politics in America, between white working-class voters and modest business organisation owners, and politicians with corporate agendas that held very little do good for those people.

By making fun of professors who spoke in language that most people considered incomprehensible ("The Lesbian Phallus"), wealthy Ivy League graduates could pose every bit anti-elite. By mocking courses on writers such as Alice Walker and Toni Morrison, they made a racial appeal to white people who felt as if they were losing their country. As the 1990s wore on, because multiculturalism was associated with globalisation – the force that was taking away so many jobs traditionally held by white working-form people – attacking it immune conservatives to displace responsibility for the hardship that many of their constituents were facing. It was non the slashing of social services, lowered taxes, union busting or outsourcing that was the cause of their problems. It was those foreign "others".

PC was a useful invention for the Republican right because it helped the motion to drive a wedge between working-class people and the Democrats who claimed to speak for them. "Political definiteness" became a term used to drum into the public imagination the idea that there was a deep divide between the "ordinary people" and the "liberal aristocracy", who sought to control the speech and thoughts of regular folk. Opposition to political correctness too became a fashion to rebrand racism in ways that were politically acceptable in the post-ceremonious-rights era.

Before long, Republican politicians were echoing on the national stage the message that had been production-tested in the academy. In May 1991, President George HW Bush gave a outset speech at the University of Michigan. In information technology, he identified political correctness every bit a major danger to America. "Ironically, on the 200th anniversary of our Bill of Rights, we discover free spoken communication under assault throughout the United States," Bush said. "The notion of political correctness has ignited controversy across the land," but, he warned, "In their own Orwellian way, crusades that demand correct behaviour trounce diversity in the name of variety."

A fter 2001, debates about political correctness faded from public view, replaced by arguments nearly Islam and terrorism. Simply in the final years of the Obama presidency, political correctness made a comeback. Or rather, anti-political-correctness did.

Equally Black Lives Matter and movements against sexual violence gained strength, a spate of thinkpieces attacked the participants in these movements, criticising and trivialising them by saying that they were obsessed with policing spoken language. In one case once again, the chat initially focused on universities, simply the buzzwords were new. Rather than "difference" and "multiculturalism", Americans in 2012 and 2013 started hearing about "trigger warnings", "safe spaces", "microaggressions", "privilege" and "cultural appropriation".

This time, students received more than scorn than professors. If the start circular of anti-political-correctness evoked the spectres of totalitarian regimes, the more recent revival has appealed to the commonplace that millennials are spoiled narcissists, who want to prevent anyone expressing opinions that they happen to find offensive.

In January 2015, the writer Jonathan Chait published one of the showtime new, high-contour anti-PC thinkpieces in New York mag. "Non a Very PC Affair to Say" followed the blueprint provided by the anti-PC thinkpieces that the New York Times, Newsweek, and indeed New York magazine had published in the early 1990s. Like the New York article from 1991, information technology began with an anecdote assail campus that supposedly demonstrated that political correctness had run amok, and then extrapolated from this incident to a broad generalisation. In 1991, John Taylor wrote: "The new fundamentalism has concocted a rationale for dismissing all dissent." In 2015, Jonathan Chait claimed that there were over again "angry mobs out to crush opposing ideas".

Chait warned that the dangers of PC had get greater than ever earlier. Political correctness was no longer confined to universities – now, he argued, it had taken over social media and thus "attained an influence over mainstream journalism and commentary beyond that of the old". (Equally bear witness of the "hegemonic" influence enjoyed by unnamed actors on the left, Chait cited ii female journalists saying that they had been criticised past leftists on Twitter.)

Chait's article launched a spate of replies about campus and social media "cry bullies". On the encompass of their September 2022 issue, the Atlantic published an article by Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff. The championship, "The Coddling Of the American Heed", nodded to the godfather of anti-PC, Allan Bloom. (Lukianoff is the head of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, some other organisation funded by the Olin and Scaife families.) "In the proper name of emotional wellbeing, college students are increasingly demanding protection from words and ideas they don't like," the article announced. It was shared over 500,000 times.

These pieces committed many of the same fallacies that their predecessors from the 1990s had. They ruby-red-picked anecdotes and caricatured the subjects of their criticism. They complained that other people were creating and enforcing speech communication codes, while at the same time attempting to enforce their own speech codes. Their writers designated themselves the arbiters of what conversations or political demands deserved to exist taken seriously, and which did non. They contradicted themselves in the same fashion: their authors continually complained, in highly visible publications, that they were existence silenced.

The climate of digital journalism and social media sharing enabled the anti-political-correctness (and anti-anti-political correctness) stories to spread even further and faster than they had in the 1990s. Anti-PC and anti-anti-PC stories come up inexpensive: because they concern identity, they are something that whatever writer tin can accept a take on, based on his or her experiences, whether or not he or she has the time or resources to report. They are as well perfect clickbait. They inspire outrage, or outrage at the outrage of others.

Meanwhile, a strange convergence was taking place. While Chait and his fellow liberals decried political correctness, Donald Trump and his followers were doing the aforementioned matter. Chait said that leftists were "perverting liberalism" and appointed himself the defender of a liberal eye; Trump said that liberal media had the organization "rigged".

The anti-PC liberals were then focused on leftists on Twitter that for months they gravely underestimated the seriousness of the real threat to liberal discourse. It was not coming from women, people of colour, or queer people organising for their civil rights, on campus or elsewhere. It was coming from @realdonaldtrump, neo-Nazis, and far-right websites such every bit Breitbart.

T he original critics of PC were academics or shadow-academics, Ivy League graduates who went around in bow ties quoting Plato and Matthew Arnold. Information technology is difficult to imagine Trump quoting Plato or Matthew Arnold, much less carping almost the titles of conference papers past literature academics. During his entrada, the network of donors who funded decades of anti-PC activity – the Kochs, the Olins, the Scaifes – shunned Trump, citing concerns about the populist promises he was making. Trump came from a different milieu: not Yale or the University of Chicago, but reality boob tube. And he was picking dissimilar fights, targeting the media and political institution, rather than academia.

As a candidate, Trump inaugurated a new phase of anti-political-correctness. What was remarkable was but how many different ways Trump deployed this tactic to his reward, both exploiting the tried-and-tested methods of the early 1990s and adding his own innovations.

Showtime, by talking endlessly about political definiteness, Trump established the myth that he had dishonest and powerful enemies who wanted to prevent him from taking on the difficult challenges facing the nation. By challenge that he was being silenced, he created a drama in which he could play the hero. The notion that Trump was both persecuted and heroic was crucial to his emotional appeal. Information technology allowed people who were struggling economically or angry about the fashion lodge was changing to see themselves in him, battling confronting a rigged system that made them feel powerless and devalued. At the aforementioned time, Trump'south swagger promised that they were stiff and entitled to celebrity. They were great and would be great again.

2d, Trump did not simply criticise the thought of political definiteness – he really said and did the kind of outrageous things that PC culture supposedly prohibited. The showtime wave of conservative critics of political correctness claimed they were defending the status quo, but Trump's mission was to destroy it. In 1991, when George HW Bush warned that political correctness was a threat to free oral communication, he did not cull to practise his free speech communication rights past publicly mocking a homo with a disability or characterising Mexican immigrants every bit rapists. Trump did. Having elevated the powers of PC to mythic status, the draft-dodging billionaire, son of a slumlord, taunted the parents of a fallen soldier and claimed that his cruelty and malice was, in fact, courage.

This willingness to exist more outrageous than whatever previous candidate ensured not-stop media coverage, which in turn helped Trump attract supporters who agreed with what he was proverb. Nosotros should not underestimate how many Trump supporters held views that were sexist, racist, xenophobic and Islamophobic, and were thrilled to feel that he had given them permission to say so. It'due south an old play a joke on: the powerful encourage the less powerful to vent their rage against those who might accept been their allies, and to delude themselves into thinking that they have been liberated. It costs the powerful nothing; it pays frightful dividends.

Trump drew upon a classic element of anti-political-correctness by implying that while his opponents were operating according to a political calendar, he merely wanted to do what was sensible. He made numerous controversial policy proposals: deporting millions of undocumented immigrants, banning Muslims from entering the US, introducing stop-and-frisk policies that have been ruled unconstitutional. But past responding to critics with the accusation that they were simply being politically right, Trump attempted to place these proposals beyond the realm of politics altogether. Something political is something that reasonable people might disagree about. By using the adjective as a put-down, Trump pretended that he was interim on truths and then obvious that they lay across dispute. "That's just common sense."

The most alarming part of this approach is what information technology implies well-nigh Trump'south mental attitude to politics more broadly. His antipathy for political definiteness looks a lot like contempt for politics itself. He does not talk about diplomacy; he talks nigh "deals". Debate and disagreement are central to politics, nonetheless Trump has made clear that he has no time for these distractions. To play the anti-political-definiteness card in response to a legitimate question about policy is to shut down discussion in much the same way that opponents of political correctness have long defendant liberals and leftists of doing. It is a style of sidestepping debate by declaring that the topic is so lilliputian or and so contrary to common sense that it is pointless to discuss information technology. The impulse is authoritarian. And past presenting himself as the champion of common sense, Trump gives himself permission to bypass politics altogether.

At present that he is president-elect, it is unclear whether Trump meant many of the things he said during his campaign. But, so far, he is fulfilling his pledge to fight political correctness. Last week, he told the New York Times that he was trying to build an administration filled with the "best people", though "Non necessarily people that volition exist the most politically correct people, because that hasn't been working."

Trump has as well continued to cry PC in response to criticism. When an interviewer from Politico asked a Trump transition team fellow member why Trump was appointing and so many lobbyists and political insiders, despite having pledged to "drain the swamp" of them, the source said that "one of the most refreshing parts of … the whole Trump style is that he does not care about political correctness." Patently information technology would have been politically correct to hold him to his campaign promises.

As Trump prepares to enter the White House, many pundits accept concluded that "political definiteness" fuelled the populist backlash sweeping Europe and the United states of america. The leaders of that backlash may say so. But the truth is the opposite: those leaders understood the ability that anti-political-correctness has to rally a class of voters, largely white, who are disaffected with the status quo and resentful of shifting cultural and social norms. They were not reacting to the tyranny of political definiteness, nor were they returning America to a previous phase of its history. They were not taking anything back. They were wielding anti-political-correctness as a weapon, using it to forge a new political landscape and a frightening future.

The opponents of political correctness e'er said they were crusaders confronting authoritarianism. In fact, anti-PC has paved the way for the populist absolutism now spreading everywhere. Trump is anti-political correctness gone mad.

-

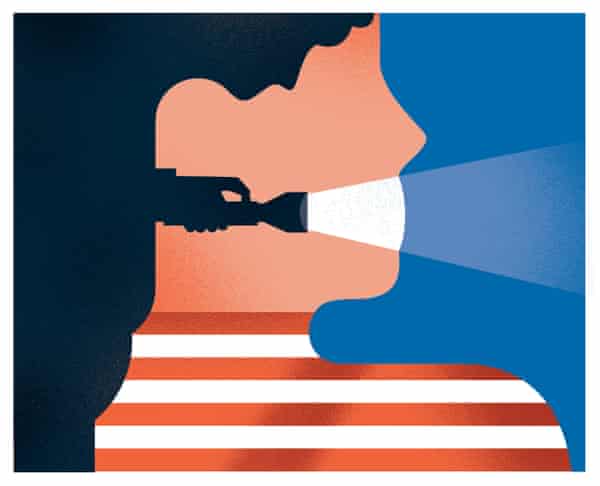

Main illustration: Nathalie Lees

Follow the Long Read on Twitter at @gdnlongread, or sign upwards to the long read weekly email here.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/30/political-correctness-how-the-right-invented-phantom-enemy-donald-trump

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Im Against Political Crectnees It Allows Me to Be Racist Again"

Posting Komentar